KAZEM GHOLAMI: WOES OF AN IRANIAN WRESTLING LEGEND IN POLITICAL EXILE

On a muggy Philadelphia afternoon in July, in a gym full of yawning teenagers staggering through post-lunch lethargy, Kazem Gholami could be anybody’s grandfather. The bald 64-year-old Iranian wrestling coach saunters around with baggy blue gym shorts hiding his pale kneecaps and a loose orange T-shirt draping his shoulders with the weight of stagnant air. He watches the young grapplers awkwardly search for balance and strength at a summer wrestling camp, chuckling as several boys body slam one another in some kind of loosely organized, exceptionally physical version of Tag. The black and green Asics Tigers on Kazem’s feet are at least 15 years old and look like they’ve been trash-picked.

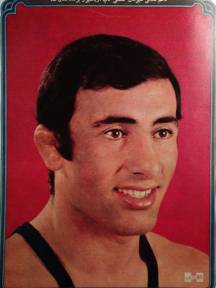

But the bulbous balloons of hardened fluid in his cauliflower ears—with coarse black hairs sprouting like weeds through a sidewalk crack—suspend a wide and glowing smile and tip you off that this man has seen battle. While demonstrating hand fighting techniques to a gym of 35 wrestlers sitting Indian style on the squishy blue and white mat at a private Quaker school, Kazem’s grip locks on my wrist, immobilizing the whole left side of my body like hardened cement. This rigid vise is sturdier than typical tremors old man strength—residual might from his days as a member of the Iranian national team.

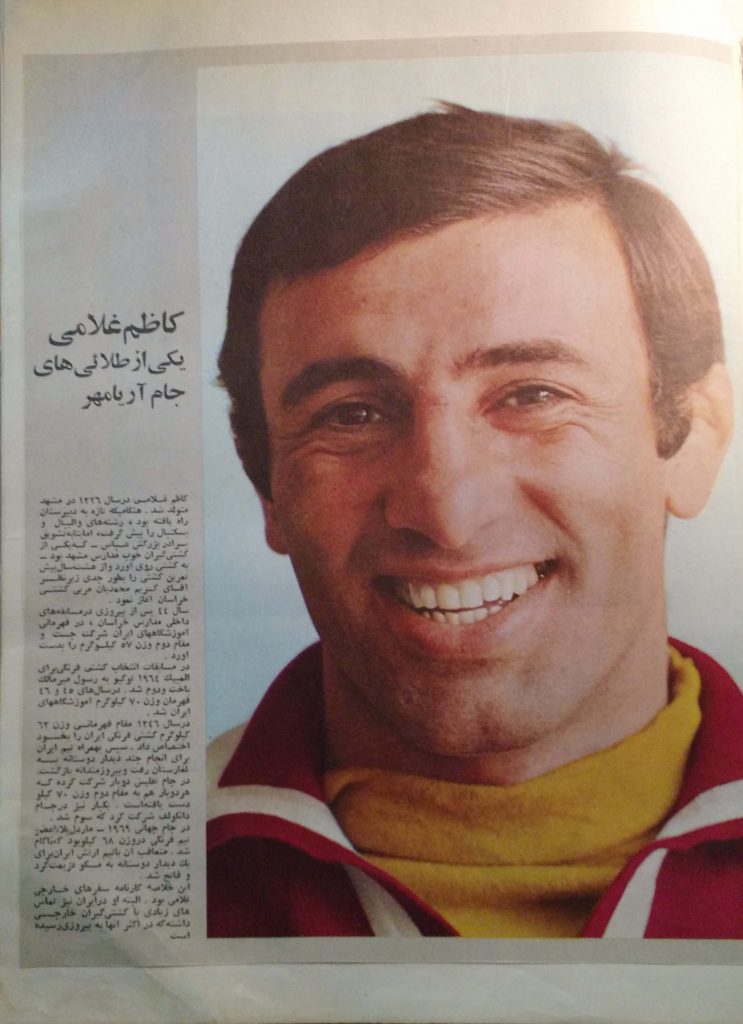

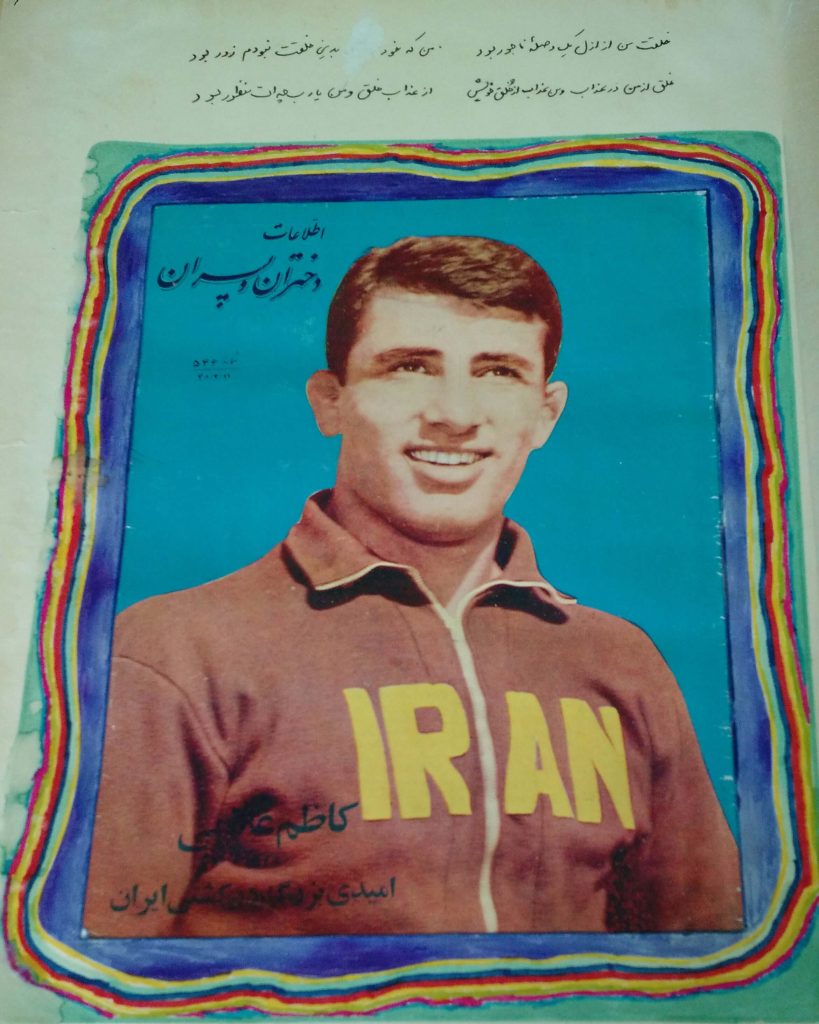

That was from 1965-1974, when he lived the honorable life of a celebrity and hero under Iran’s brightest limelight. Wrestling is on par with the military as one of the only avenues for upward social mobility in their society, so top wrestlers have always been idolized.

In Iran, movie stars and pop singers are not the ones publicly lobbying against the government for civil justice. It’s the country’s most accomplished wrestlers who carry the respect and trust of their fellow citizens, and they’re traditionally expected to take a stand against the higher powers for political and social advocacy.

But that comes with great risk.

When Iranian wrestlers make the national team and perform well, they’re traditionally rewarded with government jobs and plots of land. However, corruption seeps into every corner of this society. Kazem repeatedly refused secret service jobs that required him to spy on the Iranian people. In 1971, the head of the Department of Physical Education and Sport in Mashhad (Kazem’s home city) reallocated this wrestler-promised land to the chief of police, the mayor, and a military leader, all to secure his own political position. Kazem entered this man’s office with a handgun, demanding he give the land back to the people who needed and deserved it most. The official fainted and, soon after, transferred to a new job in Tehran, which he secured with a summer home gift to the city’s mayor.

The local police department knew Kazem and saved him from imprisonment and prosecution, but Kazem had been actively speaking out against the government’s regular social injustice against the people for years and this was the perfect moment to hit him where it hurt. Soon after, during halftime at a large soccer game in Tehran, it was announced that the Shah had banned Kazem Gholami from wrestling, prohibiting his attendance of the 1972 Olympic games. Kazem was in his prime, as well as the same weight class as America’s greatest wrestling icon and gold medalist, Dan Gable, but the matchup never came to be. After the announcement, a newspaper ran a brief editorial pleading the Shah to forgive Kazem and let him wrestle again. Flanking the letter is a doleful picture of Kazem hunched over in a light colored suit. It may be the only photograph in existence where his face is not lit up with a smile.

Kazem went to England for a few years and returned to Iran in 1980, post-revolution, to attend a large wrestling tournament and give a speech while leading the crowd in some kind of traditional aerobics exercise. Instead of saying the typical prayers and thanking leaders for all their blessings, Kazem lashed out against the new government leadership and accused them of quickly falling back into all the torturously corrupt practices of the old regime.

That night, a former coach came to Kazem’s mother’s house and tipped him off that the government was coming for him. He needed to leave. Kazem grabbed his scrapbook and some clothes and took a bus to the Turkish border, where he crossed by foot. He hasn’t been back to Iran since, but his brother was later able to smuggle out Kazem’s locked treasure box of gold medals that now sits in the back corner of a wooden bookshelf in Kazem’s home.

Kazem speaks matter-of-factly about his past. He can never go back to Iran, where he’s sure he’d be killed. Despite having to visit his family and old friends in outpost countries like Turkey and Tunisia, he lives a comfortable suburban life with a wife, stepdaughter, and an Oriental rug dealing business. As a coach, he’s infected many young grapplers with his passion for the sport and turned a dismal high school team into a small but decent squad that has seen exponential improvement for an institution that puts little emphasis on sports. Except when barking out stern commandments during warm-up drills, Kazem wears the biggest smile in the room.

But when I addressed wrestling’s biggest crisis, the recent threat of an Olympics without it, his eyes tear up and he taps his foot with angst. “When I heard it was going to be considered to eliminate [sic] from Olympics, I thought suddenly, ‘My God, I am wrestling for what?’” he says in a thick Farsi accent. “You work hard all year round and you want to reach the goal of being Olympic champion and there is no Olympics, so why I’m wrestling? I cannot believe it or imagine it or accept it…These [original] sports, they are what the ancient people did for survival, like running for their life or wrestling a bear.”

In February of 2013, the International Olympic Committee elected to drop wrestling from the 2020 games due to a supposed lack of global popularity and low potential for broadcast ratings. The international wrestling community was dumbfounded that an original sport from the games in Ancient Greece would even be considered for elimination to make way for activities like wushu and rollerblading. Having narrowed down the shortlist to seven sports in St. Petersburg, Russia, in May 2013, the IOC prepared to vote again on September 8th in Buenos Aires to decide whether to include wrestling, baseball/softball, or squash as the 26thOlympic sport.

True to the nature of wrestling’s elite competitors, the reaction was swift and methodical without room for doubt or hesitation. Petitions were signed, Olympic champions returned their gold medals in protest, and the governing body of international wrestling—FILA—appointed new president Nenad Lalovic to embark on an aggressive publicity campaign to influence the IOC and promote the sport globally. Bill Scherr, USA’s 1985 Freestyle World Champion and 1988 Olympic bronze medalist, took the helm as chairman of the Committee to Preserve Olympic Wrestling (CPOW), which has been instrumental in “working with FILA to let them know they need to change the presentation of the sport, the rules, and the governing structure.”

The signature event of this effort was the 2013 Rumble on the Rails spectacle in New York City’s Grand Central Station. Russia, Iran and the USA national teams put on a spirited exhibition for charity. USA beat Russia 8-1 in matches, but fell hard to Iran 6-1. Perhaps the most notable anecdote of the whole event was the fervor of loud, incessant chanting from the sweaty Iranian fans amassed in the top section of the temporary bleachers. They waved flags and sounded air horns while screaming words of encouragement to their athletes in Farsi.

The same vibe was abuzz this past March, when the Iranian team descended upon Los Angeles to secure their third consecutive World Cup title, besting the Russians 6-2 in matches and the US 5-3 while a fervent Iranian national anthem sounded on American soil.

This is quintessential Iranian passion for a sport that’s deeply ingrained in their culture. “Wrestling is kind of the historical DNA of Iran,” says Dr. Farhad Kazemi, Professor Emeritus of politics and Middle Eastern studies at New York University. “It is intertwined dramatically with the culture and the history of that society.”

In Persian mythology, notably the Book of Kings, legendary heroes like Rostam wrestled their foes in epic battles. Imam-Ali, cousin and son-in-law of Islamic prophet Muhammad and the first man to accept Islam, was said to be a great wrestler. But most importantly, these figures “are primordial heroes whose exploits and life shape Iranians’ view of decency and justice,” writes Dr. Houchang Chehabi, Boston University professor of International Relations and History and the first academic historian of Iranian sports. The most honorable distinction in Iranian culture is that of a “pahlvan”, which Chehabi describes as “not a mere champion…but also a moral exemplar who is just, fair, self-abnegating and kind to the weak.”

The most exemplary pahlvan of modern times was the great Gholamreza Takhti, Iran’s 1956 Olympic gold medalist and 1961 world champion with several other international medals. Takhti came from a destitute family as an anti-regime national who used his high-profile status as Iran’s most successful athlete for immunity in open defiance of the oppressive Iranian government.

But in 1962, all this came to a head when a massive earthquake shook the Qazvin area west of Tehran. Tahkti and his entourage from the National Front led an independent relief effort that personally delivered donations to the victims in a fleet of trucks, refusing to hand them over to the Red Lion and Sun, Iran’s Red Cross, for fear that the money and goods would be misallocated by corrupt officials. There was a great deal of mistrust in the regime and the people idolized Tahkti for his benevolence, but mysterious circumstances surround his supposed 1968 suicide in a hotel adjacent to the headquarters of SAVAK, Iran’s secret police.

While alive, Takhti refused offers to become a member of the corrupt parliament, star in movies, or accept lucrative shaving razor endorsements. “Takhti personified kindness, grace under pressure, altruism, generosity, forgiveness, a concern for common people, and inner purity in an environment dominated by greed, duplicity and jealousy,” writes Dr. Chehabi. Pahlvan is a distinction given by the people (not the government) and Takhti was truly idolized by the Iranians citizens, including Dr. Kazemi, whose family summered in the same neighborhood as Takhti and would bow down whenever they saw him.

Kazem loves telling the story of Takhti to his young athletes and expounding wrestling as not just a game we try to win. “He emphasizes it as more of a lifestyle than a sport or a job,” says Jesse Furukawa, whom Kazem coached from 2008 to 2010. So as a rising star in the Iranian wrestling world, Kazem had some mighty big boots to fill. Wrestling accomplishments were one thing, but to be a modern exemplar of virtue, chivalry, and humble service to others proved to be a great deal of responsibility in pre-revolution Iran.

Most of the local high school wrestlers are clueless to Kazem’s storied past when he voluntarily shows up to impromptu workouts. But a lucky few get to glimpse his prized scrapbook. It’s at least three inches thick and the size of an atlas, one of the only possessions Kazem brought with him when he fled Iran in 1975. Packed with articles mostly written in Farsi, the book flips from right to left and opens with several yellowed newspaper photos of a handsome, rather lean young Kazem sporting a full head of hair. The photos show him back-arching opponents overhead and getting his hand raised in packed stadiums large enough for soccer games. His opponents hang their heads with the shame of defeat. They are national team veterans, 6-time world champions including USA’s Olympic silver medalist Lloyd Keasner, and Iranian Olympic gold medalist Abdollah Movahed. Kazem placed several times at the World Championships and won both the Tbilisi and Tehran tournaments—arguably the two toughest in the world, since other powerhouse countries like Russia can bring as many competitors as they want.

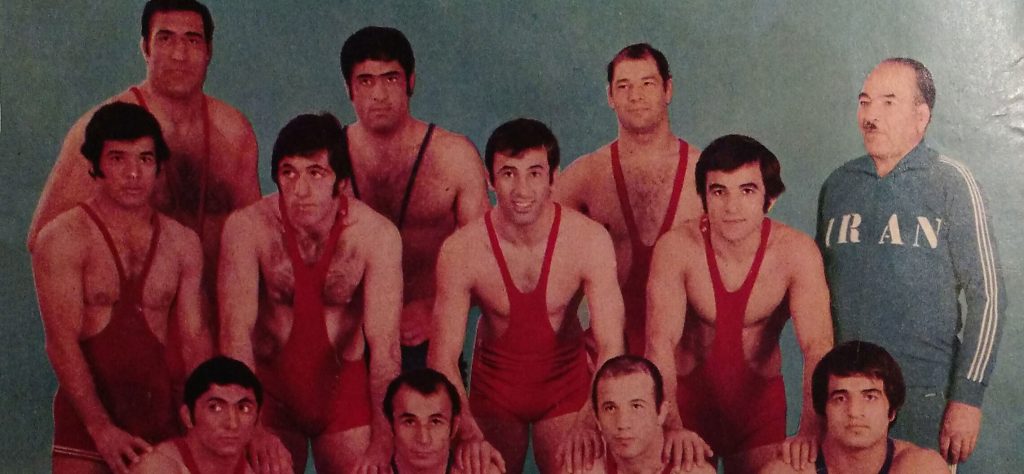

Towards the end of the scrapbook, Kazem flips to a composite of the 1969 Iranian national team. He goes through the hard, chiseled faces and points out at least six that are now dead—one of whom died mysteriously with his wife and two children in a bathroom. “No one knows how it happened, but he was already politically motivated,” Kazem says.

Given the power and influence of these athletes, the Iranian government has always kept a close eye on the top wrestlers. “In a dictatorship regime, they don’t want anyone to be popular,” says Kazem, “They are scared from somebody like him [sic].”

Although the Iranian press has long been heavily censored, an independent newspaper managed to run political cartoons in which a representative of the people touts their loyalty to Kazem over that of the prime minister and senators and refuses to give Kazem up for some kind of duty or service. The newspaper was soon shut down.

A few of the scrap book photos show Mohammad Rezā Shāh Pahlavī and his wife, Farah Pahlavi, attending Kazem’s matches, much like Mahmoud Ahmadinejad attended the World Cup in Tehran in February 2013. These are certainly gestures of support, but they also come with the expectation that wrestlers representing Iran should submit to their country’s government. Another Iranian wrestling great and 1956 Olympic gold medalist, Emam-Ali Habibi, chose to comply and accept a seat in parliament—a dangerous offer to refuse.

You won’t see Bill Scherr’s 1985 World Championship finals opponent, Mohammad Hassan Mohebbi, in any record books with his silver medal. That’s because the Iranian walked off the podium at the beginning of the U.S. National Anthem. He later told Scherr through an emissary that he meant no disrespect, but that there would be serious repercussions from the Iranian government if he had participated in the ceremony. Just like any powerful thing, wrestling’s influence can be harnessed for good or evil.

In July of 2007, Iranian human rights blogger and pro-democracy activist Potkin Azarmehr reported having helped Greco-Roman wrestling champion Pourya Fazlollahi escape the country after being brutally beaten in a secret detention center. Allegedly, Pourya and his brother had been spreading political flyers in support of the pro-human rights Iranian prince Cyrus Reza Pahlavi, son of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, who is technically still heir to the Persian throne and has been living in exile since 1979. Fazlohalli now lives in London, although it’s unclear what happened to his brother.

Kazem still supports the People’s Mujahedin of Iran (MEK), a leftist opposition movement that advocates the overthrow of the current Islamic Republic of Iran. He’s been used as a sort of celebrity endorsement for many years.

So what would an Iran without Olympic wrestling look like? Aside from a whole nation of fanatical supporters without much cause for international athletic pride (half of Iran’s medals at the 2012 London games were in wrestling), it would be one less nonviolent outlet for the country’s passion and enthusiasm. It’s also one less area of commonality they share with the rest of the world. Sport is a rare bridge between Iran and other nations with whom they have otherwise very turbulent political relationships, especially the United States. Aside from wrestling, there’s virtually no other public circumstance in which the US and Iran publicly display any positive associations with one another. It’s the sole avenue our two cultures have for acceptance and understanding of one another. Iran respects the US for it’s wrestling, and we have no choice but to do the same when they come into Grand Central Station and whoop us 6-1. Then we shake hands.

There’s been talk of wrestling’s potential for use in ping-pong diplomacy, much like table tennis broke the ice for talks between the United States and China in the early 1970’s. Almost 20 years after the Tehran embassy hostage crisis, the 1998 American national wrestling team was the first group of American athletes to compete in Iran since the calamity. American Jordan Burroughs beat Iran’s Saeed Goudarzi for the 163-pound gold medal two summers ago and a photo of the two men hugging became an iconic image from the 2012 London games.

“For many that are suffering contention outside of the arena, sport tends to be able to be used as a social vehicle for change,” says Bill Scherr. “Wrestling does have a transformative effect that’s interwoven in all these cultures. When you play by the same rules and walk away [from a match], it’s harder to hate someone with the respect you’ve gained from them on the playing field.”

Ultimately, it’s up to policy makers and nation leaders to directly shape new diplomatic relations between the US and Iran, but having that bond will continue to be a powerful symbolic relationship bringing two opposing worlds a little bit closer.

On a late summer evening, Kazem and I demolished a large dinner of Russian pilaf and sweetbread with three obscure types of meat. When we ran out of wrestling stories, Kazem fell asleep at the table slumped over with his mouth hanging open. Wrestling is the only thing I have in common with this man and the only reason I had to get back in touch with him. Wrestling connected our individual lives and opened a door for me to learn a great deal about Iran’s people, history, and values. And fortunately, this door will remain open. Thanks to the sport’s latest victory on September 8th ۲۰۱۳, wrestling will stay in the Olympics through at least 2024 and continue connecting unlikely people through the strong passions and interests they share.